By Jean Shiomoto and Ted Fong

Next year marks ACC’s 50th Anniversary, an important milestone for the community achieved through people like you, our donors, supporters, volunteers, sponsors, and dedicated staff over the past 50 years.

We are grateful to have Gloria Imagire, longtime volunteer, supporter, and past ACC Board Member, spearheading gathering people in the community who laid the foundation for ACC. To date, we’ve produced three online programs featuring conversations with May O. Lee, June Otow, Peggy Saika, Randy Shiroi, Harriet Taniguchi, Frances Lee, Hach Yasumura, Donna Yee, Brian Chin, Phil Hiroshima, Harold Fong, Raymond Lee, and Lillie Yee-Shiroi, each sharing their memories as we record ACC’s rich history. In addition, Gloria has been busy doing one-on-one interviews with people like Barbara Sotcan, Amiko Kashiwagi, Carol Seo, Jiro Sakauye, Jan Morikawa, Courtney Goto, Naomi Goto, Margaret Fujita, and Helen Quan as they go down memory lane sharing what they did and whom they worked or volunteered alongside.

In this issue of ACC News, we share with you the early beginnings of the grassroots call to action captured from conversations with them, recalling their vision, dreams, and involvement as they understood the need for care, services, and housing for the elderly.

Most people today are unaware that the seeds of ACC were planted by young Asian activists in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Their ranks included students from UC Davis, Sacramento State College, and Sacramento City College, along with faculty members. They were empowered by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, emboldened by the protests of the Vietnam War, and deeply concerned about allocation of public resources to Asians and non-English speaking immigrants in their communities. Several of the student leaders were pursuing degrees in social work and Asian American Studies, programs that were trending on college campuses.

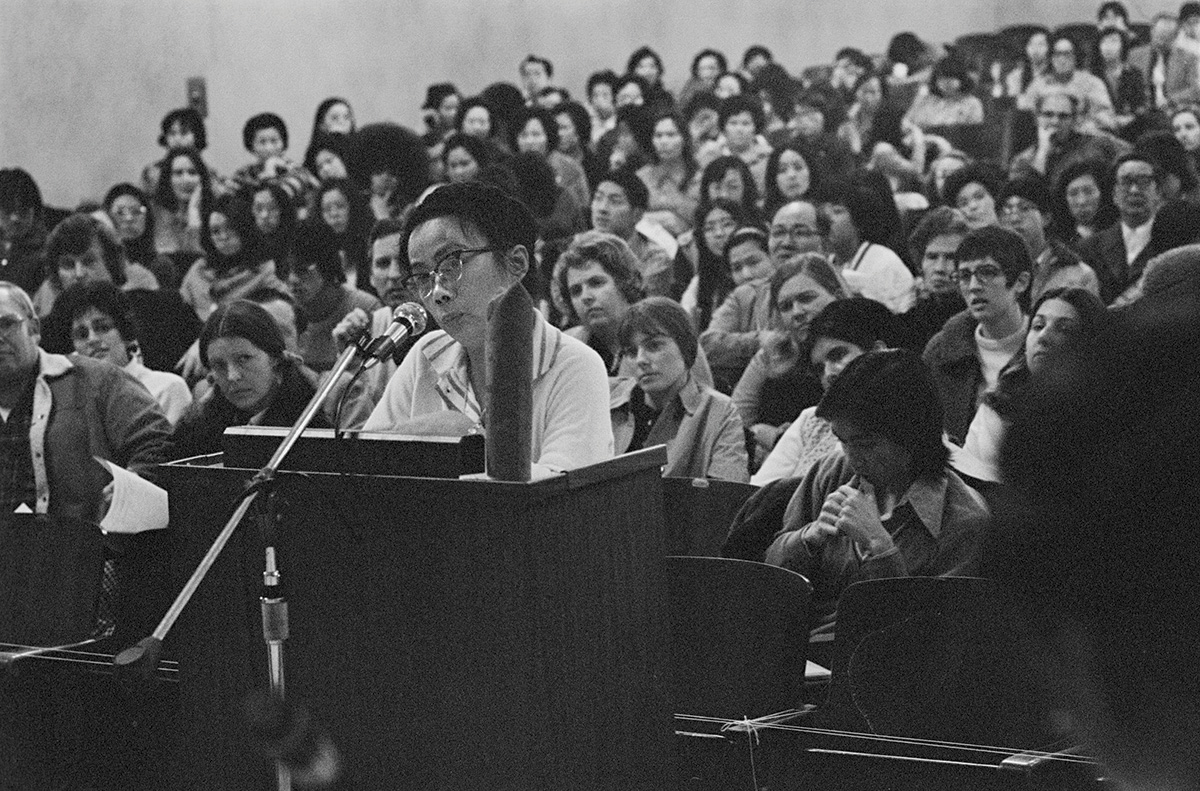

In 1969, they banded together to form Asian Community Services (ACS), not just to advocate for the rights of minorities, but also to provide services for the underserved. They confronted United Way for collecting money in the community but not investing it in social services programs to help Asian immigrants. They staged protests at Fantasia Miniature Golf Course for their use of racist pictures and slogans. They rallied the Asian community to prevent the closure of William Land School. They were community builders, launching recreation programs for the elderly and providing tutoring services for immigrant children.

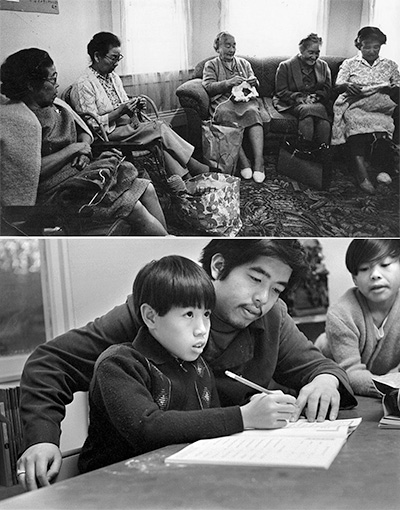

In 1970, ACS set up its field office in what was then known as the Yellow House on T Street, which belonged to the Parkview Presbyterian Church. People like Lillie Yee and Randy Shiroi began tutoring Chinese immigrant kids attending William Land School. Margaret Fujita taught ceramics, Etsu Wakayama taught calligraphy, and Kiyono Ito taught knitting. They would later move to 1118 V Street.

In 1972, ACS lobbied the Sacramento City Council and secured $6,800 to fund its programs. They were backed by the Sacramento Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), Sacramento Japanese United Methodist Church, and Parkview Presbyterian Church. Actions like these dispelled any notion that ACS was a group of rebels, radicals, and troublemakers. The people who coalesced around their cause would remain involved in building ACC Senior Services over the next 50 years.

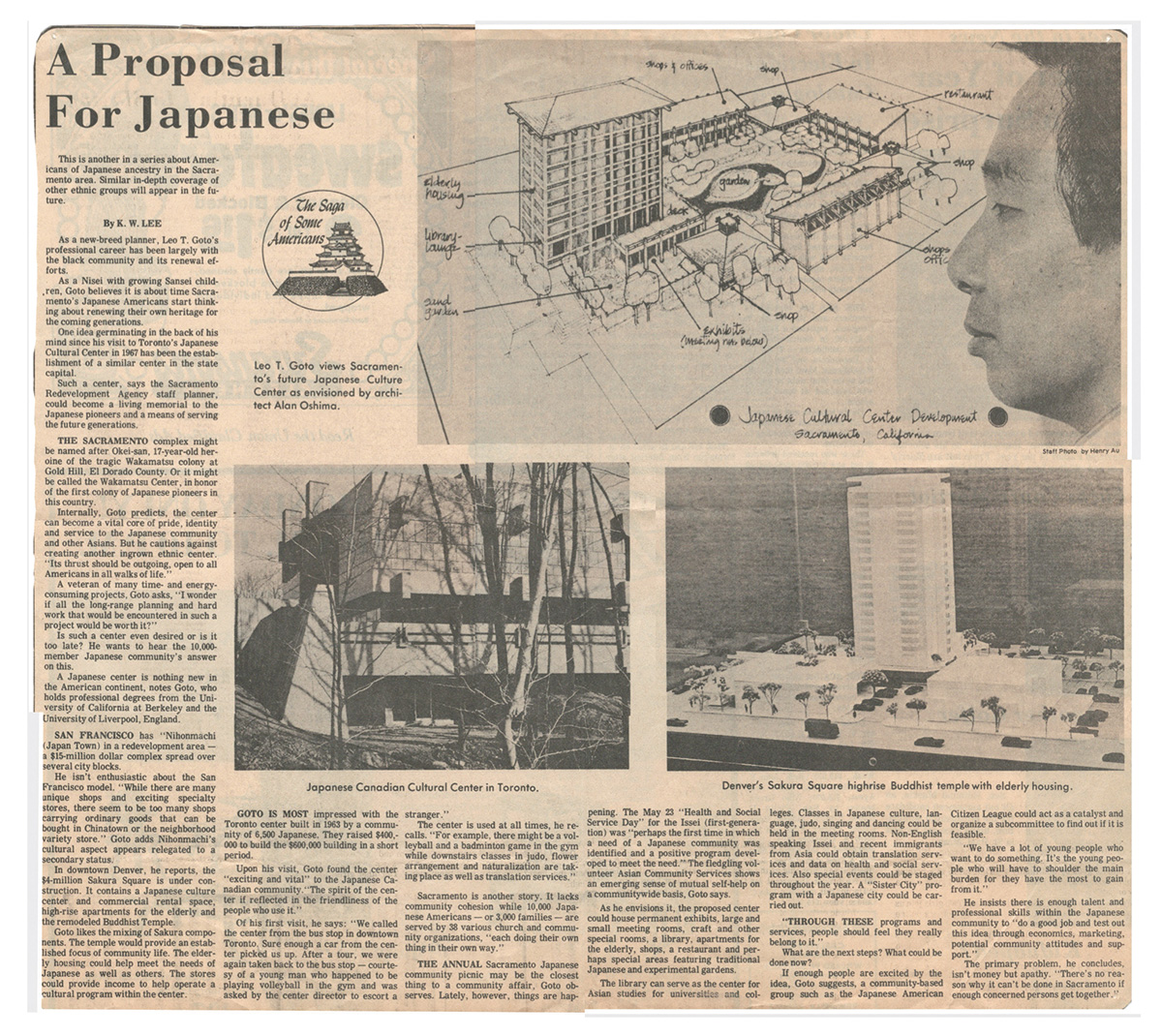

In The Sacramento Union, K.W. Lee wrote about Leo Goto’s vision of a Japanese cultural center, which included housing, healthcare, and spaces for educational and cultural activities

The early 1970s was a great awakening for the Asian community. In addition to ACS, there were other grassroots groups representing the interests of the Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Korean communities. One of these groups started as a workgroup convened by Leo Goto to study the feasibility of building a Japanese cultural center. Leo was born in Spokane, Washington, the son of a minister. He had moved to Sacramento to work as a project manager for the Sacramento Redevelopment Agency. Outside of work, he harbored a burning desire to develop a Japanese cultural center that would bring the Sacramento Japanese community together, celebrate their heritage, and look to the future. But he also wanted the development to be inclusive and “open to all Americans in all walks of life.” Architect Alan Oshima developed drawings that defined space for housing, exhibits, classes, a library, restaurants, and shops. The project caught the interest of Asian community organizations, private businesses, and churches around Sacramento.

In January 1972, 50 representatives from different organizations met and decided to form a non-profit entity. On March 1, 1972, the Japanese Community Center of Sacramento Valley, or JCC, was incorporated with help from young attorneys Phil Hiroshima, then president of JACL, and Frank Iwama. Peggy Saika, who had been involved with ACS, was selected to conduct a study to determine the needs of the community. This study took eight months to complete and was published on November 27, 1972. It identified housing, healthcare, and independent living for the elderly as key needs of the community. “For all practical purposes, the elderly housing complex and the cultural center should be within close physical proximity to each other,” the study recommended. One floor of the housing complex was to serve as “an intermediate healthcare facility.”

Several community members played dual roles in ACS and JCC – Hach Yasumura and Randy Shiroi and Peggy Saika among them – providing a connection between the two groups. Initially, some of the leaders felt that the ACS folks were rebels and radicals. While people from JCC were older and more established in their professions, eventually they took a liking to their younger counterparts in ACS for their thoughtful views and action-oriented agenda.

In September 1973, the board of ACS decided to dissolve the entity and turn over their Asian Senior Programs which served mainly Japanese Americans seniors to JCC. In its final newsletter, they stated that ACS had fulfilled its goals of 1) “raising issues that affected or were of concern to the Sacramento Asian community,” and 2) “initiating community development programs in which the people being served would eventually take over and run these programs themselves.” In their service to the community, ACS left behind the foundation for ACC’s senior services that still exists today.

Also in 1973, the Nixon administration ended federal subsidies to low- and middle-income housing projects. This was not good news for JCC, since housing was a central part of its development plan. JCC could not raise enough money to build the Japanese Cultural Center and senior housing complex. In March 1974, Leo Goto announced that the plan would be abandoned, but that it would continue to provide services to the community through programs originally developed by ACS.

The ideas unleashed by JCC’s study captured the community’s imagination. In 1979, JCC changed its name to Asian Community Center of Sacramento Valley. Chewy Ito, who was already serving as the JCC Board president since 1974, presided over the expansion of more services and the plan to provide healthcare and housing for the elderly. A gas station owner turned community organizer, Chewy was instrumental in getting business people, public officials, donors, and volunteers to support ACC’s growth. Developer Angelo Tsakopoulos donated land on Rush River Drive for the construction of ACC’s skilled nursing facility, which was completed in 1987.

People often ask, how has ACC endured for nearly 50 years? The consensus is that collaboration among the Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian minority communities ensured that the best ideas for the entire community would be brought forward and championed. Sacramento was arguably the only city in the country where this type of cross-cultural collaboration took place. Secondly, people from ACS and JCC had complementary skills and visions. ACS excited and mobilized the masses, while JCC brought in people with money and influence. Both camps were inclusive, embracing an all-Asian approach to advocacy and program development. Today, ACC Senior Services serves the Asian and non-Asian communities alike.

As ACC looks forward to the next 50 years, we will be standing on the shoulders of those who came before us. Thank you for your continued support of ACC.

Add a Comment